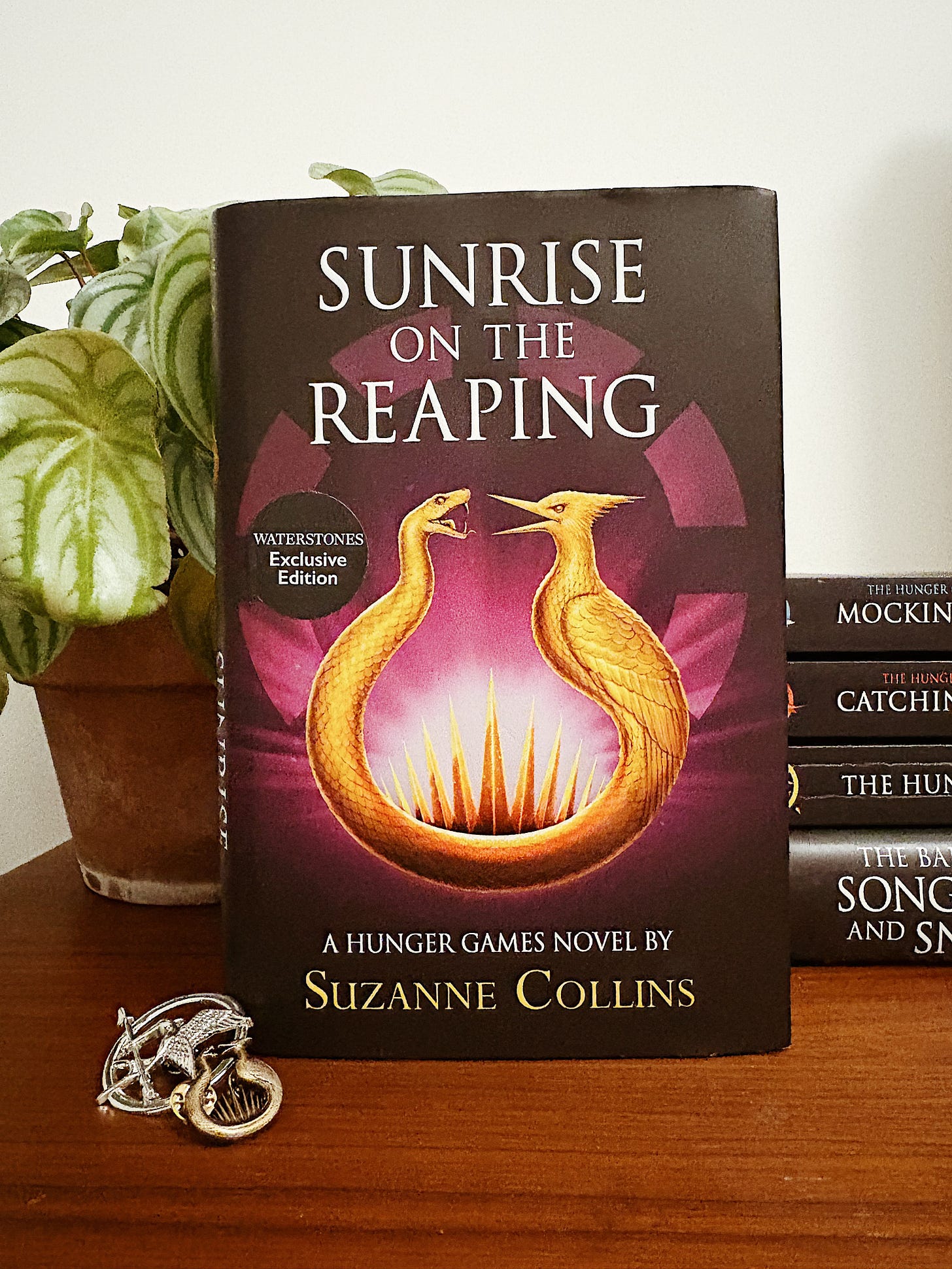

Review: Sunrise on the Reaping, by Suzanne Collins

The book 2025 needed the most, and all we had to do was cry.

Trigger warning: this post contains references to violent crime, war crime, genocide, rape, suicide.

Discovering The Hunger Games at the ripe age of 14 changed my brain chemistry. I’m far from the only person that can say that, and that is testament to the tight grip that the ruthless histories of Panem have had on avid readers, and raging feminists, alike. Much can be said about what gave The Hunger Games an edge over its dystopian contemporaries. I can speak with utmost confidence about what left a mark on me, as the eldest daughter of a post-Communist, soon to emerge as middle class, patriarchy-infused family:

The weaponisation of youth in pushing the government’s propagandist agenda - why, Ceausescu loved a flag parade enlisting primary school children on empty bellies;

How wealth discrepancies were illustrated through the ‘panem et circenses’ trope, central to the story - post-1989 Romania had since developed an unhealthy obsession with reality TV, spectacle politics, and not leaving the dinner table before licking your plate clean;

The preservation of natural and musical elements as symbols of the people, dating all the way past recorded history.

Considering the above, it’s no surprise I ADORED Sunrise on the Reaping. I’m not here to tell you what an incredible book this is, for that surely would be a waste of your reading time in present day’s rabid attention economy.

Instead I want to talk about why this prequel to the original trilogy - focused on Haymitch Abernathy’s participation in the Quarter Quell marking the 50th edition of the Hunger Games - is very important today, and even a book we ought to hold close to our hearts in the years to come.

Warning: major spoilers ahead!

Gore Turned Up to Eleven

Sunrise on the Reaping depicts, by far, the most graphic edition of the games we’ve watched unfold to date. A painful experience from the get-go because for the purposes of the 2nd Quarter Quell, each district is forced to provide double the number of tributes usually required: two boys and two girls. We go into the book with a reasonably clear expectation of what’s about to happen: the Hunger Games can only have one victor, and Haymitch next appears in the opening volume of the trilogy. Perhaps to make up for what we know, the story spends a truly agonising number of pages breeding the reader’s affinity for various other tributes, and just as many to kill them off very slowly and in cruelly bespoke ways. Besides hacking at our heartstrings, this decision by Suzanne Collins does serve the plot: for characters like Ampert, the terrible deaths of tributes serve as a political, manipulative, and eventually vengeful narrative device.

What I read either turned my stomach or made me sob until I became a snotty mess - and that was supposed to happen. With these scenes, Collins has merely held a mirror to the commodification of violence across modern society, something we now witness in real time through around-the-clock news coverage and widespread access to social media communication. Make no mistake, this is far from a recent conversation: genocides have continued after the Holocaust. Dissidents and political prisoners have been punished in ways that make the official definition of ‘war crime’ quite unimaginative. Violent crimes have been nurtured at the very heart of our communities, in forms we’ve come to accept as the ‘norm’ and ‘how things are supposed to work’. The most recently prominent example of this is the undignified deaths of individuals with health struggles at the hands of highly exploitative health insurance companies, in countries like the United States.

Sunrise sees the first unabridged mentions of rape and suicide, which the series has only touched on previously, often using subdued wording. I believe this isn’t through sheer happenstance: Collins is telling us we can no longer look away, because endemic issues across our society and communities are now making us turn against one another, and against ourselves. And by turning away from these words, we risk denying this painful, yet familiar reality, and thus enabling it to plunge its roots farther and farther across spaces we hold both in respect and safety.

The Power of the Many, the Fear of the Few

In contrast to the rest of The Hunger Games, the great majority of the tributes participating in the 2nd Quarter Quell foster a potent sense of camaraderie, in the folds of an alliance created in response to the Careers, called the Newcomers. Past the inspiring appearance this bond maintained for most of the Games, lay a string of highly improvised seditious plans that sought the destruction of the Hunger Games, with Haymitch himself at the very heart of the insurrection, and Catching Fire and Mockingjay veteran Plutarch Heavensbee advising from the sidelines.

If the rest of the series was not clear enough, it takes a village to raise a child, and a group of starving, reckless children - and serendipitously tactical adults egging them on - to stage a coup. President Coriolanus Snow must’ve been aware of this himself, for by the time we watch Katniss go into the 74th Hunger Games, a distinct kind of desolation hangs like a dark cloud above everyone’s heads. Except maybe Gale’s, but we don’t talk about Gale. Katniss herself could not give less of a shit about driving a revolution, not until she comes to the realisation that her loved ones are in imminent danger either way.

Looking across all five Hunger Games book, it’s easy to recognise that solidarity can - and in fact, should - exist across all strata of society. From Effie Trinket’s genuine compassion to Beetee’s pained acceptance of his son’s fate, to the enigmatic intentions swirling in Plutarch’s head, the roads that brought us all here may be different, but that is far from an excuse for not understanding that change. Must. Happen. That what we have currently no longer works. Collins leaves behind no uncertain terms around the price that must be paid for change to be effective. There will be failure. Plenty of it. So much of it that will make it feel like change will never come.

And it’s at this point that we must waste no time in harnessing the energy of the collective, without which revolution is nothing more than a pipe dream. And a collective, well, it’s made of little individual voices bolstering themselves all at once.

The Rich Get Rich, and the Poor Get Poor

Considering the above, it’s safe to assume that by disbanding the collective, one can stop the revolution before it even begins. And what better way to drive individuals apart, than by showing them how different they are from one another? This has been done using many different methods, and quite often, some of these overlap - because the more division you sow, the more disrupted each attempt to reconvene becomes. Somewhat powered by the cultural grip meme culture has on us, hating the rich has become the new black. Far from me to take the moral high ground on this. I’m sat wearing my ‘Eat the Rich’ fork and knife earrings while writing this.

What tells economic discrepancies apart is that by design, the mutation of hyper-capitalism that we’re living through aims to make some richer by making us poorer. Billionaires exist because they exploit human work, and when that hasn’t been enough, they now render human work obsolete by shoving artificial intelligence down every delivery pipeline they can find, even those that are unprepared for receiving the contributions AI can provide.

There was a time when billionaires didn’t exist, and when delivery workers didn’t die on site so we could get toilet paper and lightbulbs around the clock. And Sunrise on the Reaping is very keen for us to remember that. This prequel shows a struggling Capitol that can’t organise a proper opening ceremony for the Games (not without killing tributes in the process, anyway) and where citizens do not have access to a lot of the resources and supplies we see in abundance in the opening novel to the original trilogy. As for District 12, they have an actual candy shop. We’re talking about the same district where most people can’t afford to buy bread by the time Katniss participates in her first Hunger Games.

What we learn from this depiction of Panem at the turning point of the 2nd Quarter Quell, is that wealth and class discrepancies have deepened over the years. The Districts’ disdain of the Capitol existed already because of the Hunger Games - a pretty valid reason to hate someone’s guts, if you ask me - but these discrepancies, and having to constantly tether on the very edge of survival, could only deepen this disdain. Concurrently, the Districts also run out of both material and psychological resource that could be put behind a potential revolution. Katniss herself recognises it, shortly after returning from her and Peeta’s Victory Tour. Suddenly, the power of the many doesn’t look so frightening anymore.

What Stories Will We Tell?

The Capitol’s coup de grace against the people of Panem is weaved, albeit discreetly, across the entirety of Sunrise: the insurmontable impact of propaganda. We spend the entirety of the story following Haymitch as he attempts to ‘paint a poster’ of his opposition to the Capitol, speaking truth to the opposition felt by everyone that fought to keep him alive and empowered him with the knowledge he needed to break the Quarter Quell arena. All this work, burnt to a crisp when a rewatch of the Games is aired, showing that none of Haymitch’s defiant gestures have been broadcast to the rest of the country. No-one got to see that poster - except for the people that worked to edit it out, now to be lost to the annals of time.

As readers, we do see it all, but this doesn’t mean anything. In our day-to-day lives, though, this means everything. We get the complete experience: how news are told, how history is recalled, and how it all really happened. With this all-encompassing view comes the sobering understanding that how news are told today determines how history is recalled tomorrow - and propaganda can, often will, come in to warp all we think we know about how the world works.

Propaganda is far from just a tool that dictatorships love to use. Instead, it’s kind of everywhere and by honing our critical thinking and maintaining up-to-date knowledge about the world around us, we stand a better chance at minimising the degrading impact it can have on our perspective and decision-making. The biggest mistake one can make is believing unequivocally that they are immune to propaganda.

It’s far from a surprise that Suzanne Collins herself may be so worried about the impact of propaganda in the 2020s, that she spent a significant portion of Sunrise showing us how it works. For a change for the better in this world of ours, propaganda is one of the most serious threats to look out for. And if this new Hunger Games book is not enough to convince you, then look at the US right now. And if that isn’t enough also, then I’ve got nothing else to offer you: this is as scary as it gets. Although more famous last words have been spoken.

Despite it telling a tragic story, I left Sunrise on the Reaping with a lot of hope: that even when it’s at its darkest, the world is worth redeeming. If some kids pitted against each other in a battle to the death can instead become friends and wave a middle finger in front of the dictatorship that sentenced them, surely we can come together and work on building a better society for the generations to come.

And in that spirit, I wish to know what you thought of Sunrise on the Reaping! Is this what you were expecting? And how many water bottles worth of tears have you wept throughout the last 40 or so pages?

Most importantly, if Suzanne Collins is coming back with a third prequel, which character should it be for? My money’s all out on Plutarch Heavensbee, always.

Thanks for reading.

Two Things Are Sexy: Men That Don’t Man-splain and Disclaimers.

This Is Not A Nuclear Drill sets out views and opinions by this author and this author only. The interests, views and opinions I express here do not reflect the interests, views and opinions of any other people, organisations and entities.

I do my very best to provide evidence, links and direct quotes on everything I write about. I fact-check the content I post to the best of my ability, but I’m only human and I might get things wrong. Please correct me if you spot any such errors.

Similarly, I endeavour to include trigger warnings wherever appropriate. If you spot something that you judge should have a trigger warning and it doesn’t, please flag it up in a comment and I’ll edit accordingly.

This post does not contain affiliate links.